The Future Of Food

Words Katherine Templar Lewis

Photography Rebecca Miller

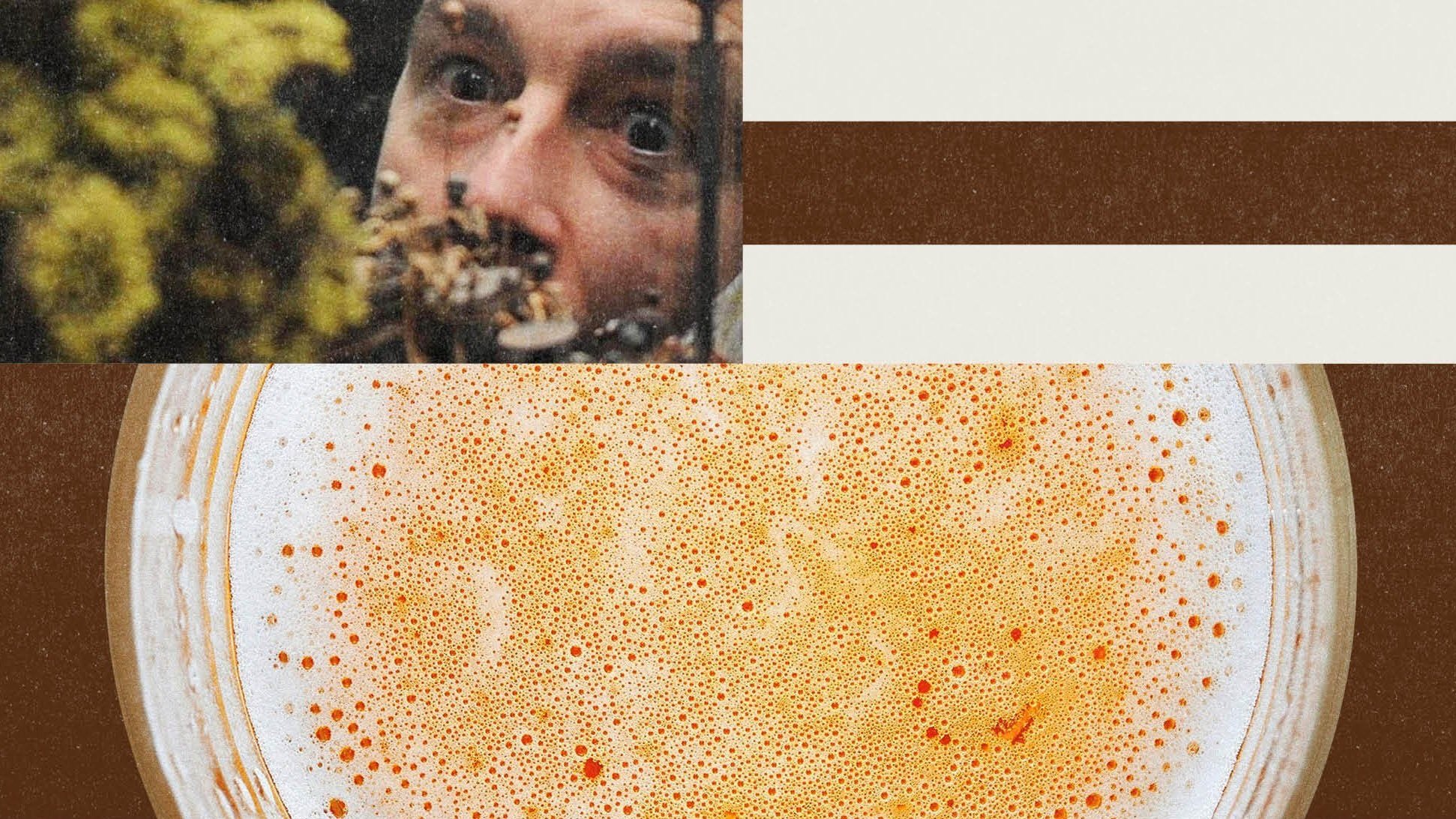

Dr. Irwin Adam Eydelnant sits at the intersection of creativity, science and global food futures.

Founder and Creative Scientific Director of Future Food Studio, he divides his time between a futuristic food experience lab in his native Toronto, and a self-sufficient 70-acre farm situated in upstate New York. Irwin is a visionary, creative scientist and future food prophet. With a background in bioengineering, he leads a studio of 20 multi-disciplinary experts to re-imagine how we interact with food. On a mission to empower individuals to see food as a medium through which we not only transform ourselves, but the worlds around us, he believes that ‘every mouth today will change the world tomorrow’. His time is spent creating global art installations and moments of ‘delightful disorientation’, which have included a machine that pours drinks in response to emotion, the deconstruction of beverages into edible clouds, large multi-scale projection map dining experiences, and an interactive ice cream factory. Oh, he holds the record for the world’s largest sandwich. The UK’s own creative scientist, Katherine Templar Lewis caught up with Irwin to discuss sandwiches, smoke and the future of food.

Irwin hello, how are you today?

Good, really good, I’m freshly returned to America from Paris and back in my studio.

Great, so can we talk about sandwiches? One in particular that you made… The world’s tallest sandwich?

Ha, yes. It was the most ridiculous thing ever. It was made out of mustard and salami slices. It was a very specific record, the world’s most layered sandwich. A client asked me to get the world record and I said okay. Honestly though it wasn’t even that big. I mean, it was actually pretty small, 60 slices. But it was fun. It sounds crazy, but it falls under the category of everything I do. I create moments with food which makes people’s brains turn on for a second, and see it in ways that they just haven’t thought about before.

Like the pourable, edible smoke?

The edible clouds? Yes we deconstructed beverages and reconstructed them as pourable, sippable, clouds.

Needle scratch noise — let’s pause things here. I’m a scientist myself so I know he actually made clouds, not smoke. Clouds are made from tiny liquid particles called aerosols. Smoke is a mix of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and particulate matter — soot. But this is the brisket issue so… same same, but different… yeah?

Let’s get back to Irwin.

It’s the red thread of all my work, to use food to transform. So many folks move or in and around food in a very automated way. Not because they don’t care, it’s just never been part of their consideration. I always had a passion for food. I grew up on a prairie, in a hardcore Russian family, so food is communication. My first job was working at an ice cream shop. I trained as a biochemical engineer but with a passion for food and design and one day I realised they all intersect. Food fundamentally is a platform that everybody understands. It transcends religion, transcends geography, transcends culture, politics, gender identity. I found that my creative jump was really to create these moments of pause through delight. I call them moments of pleasurable disorientation, moments that allow someone to stop and choose whether or not they wish to be conscious about what they’re eating.

Right, because you work by the idea that what we eat transforms us?

Yeah. I joke that the only times we truly create on this planet are when we feed and when we fuck. Feeding is this incredible connection between the spiritual and the material. When you’re making food for someone and you share it with them, that food becomes their hair, their skin, their nails, you’re literally creating another being. And I can’t imagine anything more beautiful than that.

Or more distressing when you think of what some people eat.

Well, yes, and then that becomes the question. If we were able to share that framework with more folks, would it actually just shift how people consume food? It’s a very different perspective than our very utilitarian perspective of energy in energy out. Food actually transforms us in an individual way. What I’ve really started to recognise is that all of this revolves around epigenetics, the code that controls our DNA, and which bits turned on and turned off. Over the last decade, we’ve come to realise how much the environment around us transforms our epigenome, food included. What you eat becomes you but also changes you, and those changes are passed down generations.

So what does this mean for the future of food?

Well, wouldn’t it be interesting to think beyond just the nutritional contents of food, but its epigenetic and health impact on us as well? I call the press juice problem. Someone walks into a juice shop. How are they making a decision about the best juice to consume for their individual needs? At the end of the day, it’s marketing and branding, an arbitrary name and colour. You’re like, I want the green one. But what happens when we’re a bit better equipped to make these decisions based on where you’re at in your current nutritional physiological state. If we have this information on an individual level, how would it function on a collective level? What would the role of a grocery store become? Maybe no longer just a warehouse for food but a community centre producing the food that people actually need where they need it.

So is this the second half of your equation, every mouth transforming the world around us?

Exactly, it inevitably leads to the question of what foods and where does this food come from. The production of food is creating an environmental memory, the accumulation of CO2, carbon from soil, rainforest deforestation. It all comes from our food production choices, of which we are highly uneducated and uninformed. There’s a lot of utopian greenwashing conflating issues of health and climate change. And unfortunately the average consumer has no idea. We need to demand more information, demand that products not only be labelled with nutritional information but ecological impact information.

But about cell agriculture? Surely that’s a real eco-solution?

Well, as you know, I come from a tissueengineering background and I’m a big proponent for a shift away from intensive animal agriculture. But at the same time, I don’t know how I feel about cell agriculture any more. The elephant in the room is that it’s still being made using the foetal bovine serum, from cows. That’s the comedy of it all. We’re still extracting serum from baby cows, for lab-grown meats. There’s a lot of obscuring of fact and truth in these spaces too, purely motivated by investment.

But you’ve grown human tissues in the lab before, can we eat that!?

It’s been my question since the very beginning, why are we trying to figure out animal tissue engineering, when we actually don’t have the cell lines or technology. It’s not what tissue engineering has been trying to solve. Bio-engineering has been trying to create cells for humans. So actually it seems like the barrier entry is much lower for human tissue. I think it’s actually an appropriate consideration…

Great, but for veggies among us, I’m getting the feeling from you that it’s not all going to be vapes and insects, like you once prophesied?

You’re catching me at an interesting moment in my thinking. Part of me regrets prophesying future food technologies and ways of eating tomorrow I once talked about. A lot of it always falls into the hands of folks who understand one snippet of it, but then just over optimise in that direction. Often profit. In the 1960s we had the green revolution. We saved a billion people from the brink of starvation by creating new strains of wheat and rice that could be grown more intensively. It worked great, Nobel Prize-awarded, we felt great about it, but we didn’t consider the total impact of our actions. Suddenly we had dependency on chemical fertilisers, excess water, subsistence farmers becoming dependent on external factors to grow their food. We created this whole ecosystem that essentially collapsed our food system. It solved one problem but it really didn’t take into consideration the complexity of the food system. At the end of the day, I’m having my own little existential crisis over this because food is fucked and it’s continually being fucked. I’m writing a book and I’m pretty sure that the title will be Food Is Fucked, because as individuals, we’ve given up too much agency. Not only should we be taking an interest in food, but a responsibility too. I think COVID actually was a great moment where at least some percentage of the population woke up to that and was like, hey, wait a second. I need to actually have a little bit more skin in the game here.

Is that why you’ve decamped to a farm on the prairies?

Prior to COVID I worked on a project looking into how we can be more restorative with grain and improve people’s relationship with bread, which we’ve been eating for thousands of years. It was incredible to be on land again and working with farmers directly out in the fields. I realised I travel around the world doing projects about food, writing about food and talking about food and yet I was disconnected from the elemental part of it, putting a seed in the ground. My aim was always at some point to live on land but it was expedited by the pandemic. It’s been incredible to connect to the land, to genuinely build a relationship with it and stewardship. It’s realigned my own visions around the future of food. Now when I’m thinking about the future of food, I wonder how we can create a connected revolution? We had the greener revolution in the 1960s, but can we now create a connected revolution and really start to view food as this biological interface between us and the earth?

And maybe we start with moments of pleasurable disorientation and edible clouds?

Yes!