We Asked Award Winning Author Will Self To Write Us A Story To Open The Brisket Issue

Words Will Self

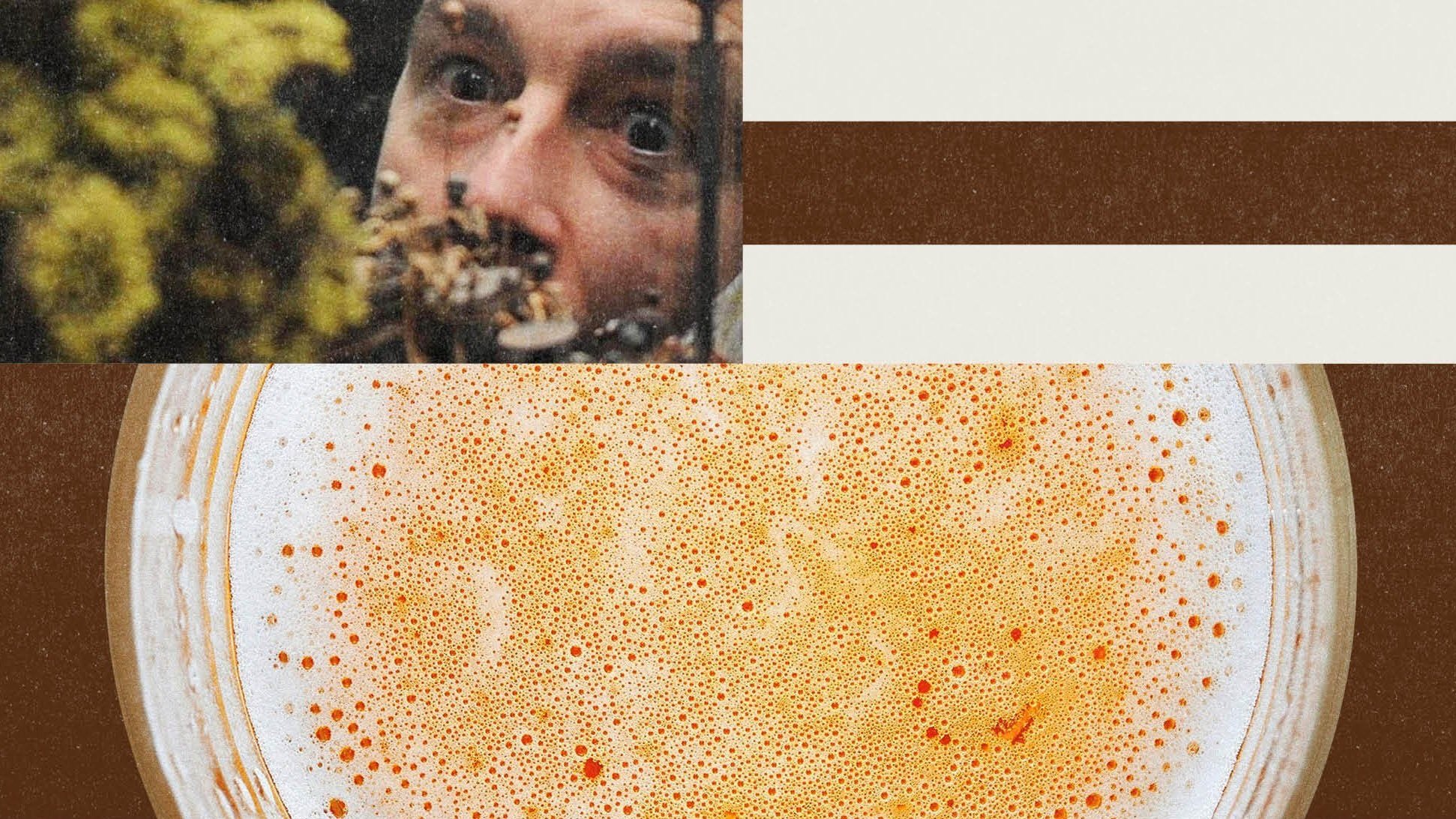

Illustration Stella Murphy

RISK IT

SLIVERS of glass — slabs of concrete... stalks of steel... Working in the City — London’s financial district since trading accounts were settled in denarii — is now a cuisinart: everything is sliced, from the very built environment itself, right down to the minuscule Parmesan-shavings-of-time during which millions are won and lost.

Gone now all soft organic shapes and motions: in the sepia-stained past, come the dinner-hour computers — as they were once known — slid down from high stools in Lothbury, Cornhill and Bishopsgate to breast the noontime smog of ten thousand coal fires, and frequent the wood-panelled dining rooms where stewed oysters slid about on platters until they were washed down with ale as brown and pungent as the industrialised Thames.

Pinioned by the baroque spires of the Wren churches, the very clouds themselves must’ve seemed smoky emanations of this writhing, overcooked little maggot-heap... The great triangular bulk of the Bank of England, with its soot-stained flanks, was the very incarnation of an imperial power, the fiat currency of which was backed not by gold... but beef. That animal scale is now altogether disrupted by the slivers of glass, the slabs of concrete — the stalks of steel... The City is nothing but a great big sandwich now, and when we break for lunch, we masses slather the streets as we stride... trot — even run full-tilt to buy one of our own.

The chasms between the new mega-structures that make of the older buildings only so much... filling... suck down vortical zephyrs that bring with them grit fine as black pepper ...salt ‘n prepper...? seasoning my cheeks as I make a dash for it, past pigeon-roosting pastrami pickers and starling rows in grey-faun high-street suiting, choking down their baps and buns and wraps. Down here at ground level everything is sliced in two: the rich and the poor, the swift and the slow, the raw and the cooked, the cops and the robbers.

‘It’s pretty hard to find,’ Cholmondeley had drawled, tipped back so far in his swivel chair that his heavy-gold hair garnished the keyboard of his computer ‘a well-kept secret — only accessible to a few initiates... my directions will necessarily be perfunctory, because I’m not sure I want you to find it...’

This, the flatulence of our workaday banter: a sad slack souring competition to find the best sandwich we can — and then keep it to ourself, while taunting the other. Because there’s always another — isn’t there, even when we’re utterly alone, we feel them inside us, in between the thick freshly-sliced bits of ourself; so it is we bite down hard and chew mechanically on... compassion. By which I mean to say — I’d have done the same to Cholmondeley, who besides being an irritation has a name that, since it’s pronounced differently from how it’s written, draws your attention insistently to the underlying structure of language itself: the signifier, what is signified, and the arbitrary nature of what you put in between them.

So... how about the extras...? I found it anyway: in the coleslaw confluence of old alleys that lie in between Gracechurch Street and Birchin Lane down at the very dead end of one of them, a dank place covered in pigeon droppings, it was hard not to think about as she thrust her pretty angry bored face at me over the countertop. I don’t know, I said, what do you suggest? With the brisket sandwich... she wrinkled up her already-retroussé nose, so that given the silver ring piercing its septum, the resemblance became impossible to ignore ...simplicity is the key: just our own mesquite sauce and a little ‘slaw.

I ate it on the steps of the Royal Exchange — and it was delicious: all that was strange and vigorous and wild and elemental seemed bound within that brioche bun. Broncos bucked on the prairies of my mind, brave warriors whooped and the buffaloes roamed past... a Big Issue seller. That’s the trouble with lunchbreaks — they’re nothing but a tranche of freedom, pressed between two slices of compulsion. And what’s it all for? More carbohydrates — we live, I think, in a sandwich world: our very being spread thinly between good... and evil... life... and death. Still, I got to crow over Cholmondeley, speckling his suit lapels with mesquite sauce as I did so.

So, I went back — and back again. Cholmondeley protested: The brisket sandwich was last month - move one… It’s your turn to challenge me with something new. new. But I’d lost interest in him, having found another other: behind the steamed-up shop window I stole my moments — because after the fifth or sixth brisket sandwich she’d begun to lecture me, quite charmingly: Even pork would be better than beef — and chicken better still, if you must... Of course, it transpired she’d forsworn meat since adolescence, and that her whole life was an ethical smorgasbord: not for her the soft carb’ compromise pressing inexorably down: there was nothing above her but the blue vaults where her compassion flew freely.

Last summer — while I was eating bridge roll after bridge roll at Glyndebourne — each one sicklier than the last: it was a works outing to the opera; a reward for restructuring the debt of a country where religious sectaries were hung up by their ankles, electrodes attached to their genitals, and slowly... smoked — she’d been suspended from a tripod of scaffolding poles in front of the Mansion House: a prime ethical cut, basted by the media, and blasted from below by pissed-off police sweating in serge.

The job in the sandwich shop was simply a means to an end — a utopian one: the harmoniousness between humankind and Gaia conceived of by analogy with a salad; and not one in which the ingredients — grated carrot, unripe cherry tomatoes, frigid lettuce inter alia — are compressed in a rigid single-use plastic dish; but a beautifully variegated massing of pine kernels and pimento, arugula and anisette, rocket and radicchio. O! Each time she leant forward to fork ‘slaw from the trays beneath the counter, or scoop pickles, or pinion slices of brisket with her tongs, I allowed my gaze to pool in the hollow of her clavicle — then overflow it, and slime down, rippling over ribs, to coat, filmily, her perfect little breasts.

She knew I was doing it — and accepted my oleaginous voyeurism, encouraged it, even, as if this were the price to be paid in return for withstanding her hoary homilies. Because we’ve heard it all before haven’t we? How the ‘national’ dish of the Lone Star state is the absolute confirmation that these bigots are what they eat: lowing, screaming whorekine, fucked over by artificial insemination, left to wander the dusty drought-scarred ranges, their cartilaginous breasts swelling as they’re shot up with antibiotics by immiserated wetbacks, much as cosmetic surgeons enhance the breasts of the wives of the red-faced NRA members who nominally ‘own’ them. And then: herded into a spiralling walkway, designed by an autist with absolute compassion — so they never see the electric bolt before it enters their bovine brains. And how humane is that, because we too never, ever see death coming.

Every bite you take... she adjured me... you absorb more of this: the very smoking of the meat is just another poisonous emission — it doesn’t matter if it’s hickory chips or high octane petroleum, the results will be exactly the same... we’re all going to choke... And I nodded, and groaned, and rolled my eyes the way we do when we’re being put in our place. But since that place was a sandwich shop in a dead-end alley in the City, I didn’t feel too bad about it, so eventually asked her out. She accepted.

And I took her to a world rather than a worldly restaurant — in Hoxton, natch’. Ponchos nailed to terracotta rag-rolled walls, waiting staff dressed like Tuareg, messes of pulses served in lenticular clay-fired dishes — mushroom juice of the least interesting kind to drink... She adored it: her pale blue eyes grew silvery and coruscated in alternation with her charming nose-ring, as she schlupped up this muck. I sat nodding, confessing to the change in me as I measured her up for the chomp: I’d missed out on my brisket sandwich at lunchtime, and let’s face it, however much the miserable veg-heads may insist — a meal just isn’t a meal without some meat in it. Then, later, in her charming little room with its peeling Extinction Rebellion posters and its sentient pot plants; after unwrapping and some fork-play between oblong duvet and oblong futon, she reared up above me... Mississippi Fred McDowell groaned from the speaker in the defunct fireplace: Big fat mama//meat shakin’ on her bones... and I reared up as well, teeth bared.