How The Chili Pepper Didn't Conquer Denmark Until It Eventually Did

Text by Matt Gross

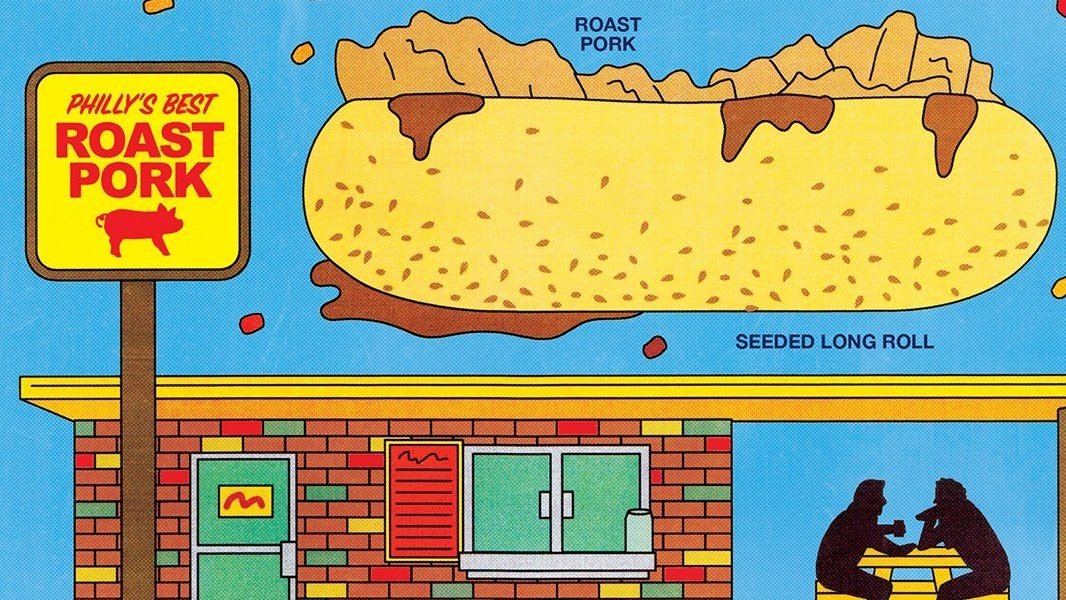

Illustrations by Katerina Kerouli

Lately, my plan is this: When they come for the Jews, I’m moving to Copenhagen and opening a Sichuan restaurant. On its face, I know, this sounds ridiculous. But we have good family friends there, and while Denmark has been ambivalent about refugees in recent years, it protected Jews during World War Two, so I’m relying on that. Also, I’m halfway decent at Sichuan cooking. My mapo tofu is highly satisfying, I’ve got a secret recipe for water-cooked fish, and a friend of mine recently pronounced my chili oil “fucking delicious.”

And maybe that’s the most ridiculous thing: spicy Sichuan food in Denmark?!? Because while Denmark has, over the last decade, transformed itself into a top culinary destination (thanks, Noma!), it remains a land almost untouched by the chili pepper.

This is weird. The chili pepper is, by most accounts, the world’s most popular spice, an essential component of cooking from the Americas (it originated in what’s now Bolivia, and was first domesticated in what’s now Mexico) to all over Africa and Asia, and much of Europe—think Spanish pimentón and Hungarian paprika. And that conquest took place in just the last 500 or so years, as sailors who’d encountered this New World fruit spread it to every corner of the globe, aided by Arab spice traders, botanically minded monks and aristocrats, the occasional military invasion, and migratory birds (which are unaffected by capsaicin, the chemical that causes chilies’ signature burn). And yet Denmark, along with a handful of other countries, did not get into chilies back then, and is only just starting to today. Why?

“You got three bad years in a row and forget it—I mean, that's it. So you tend not to experiment with new stuff.”

To answer that question, Carol Gold, a historian and the author of Danish Cookbooks: Domesticity and National Identity, 1616–1901, talked to me not about chilies but about potatoes. They’re everywhere, a nutritious staple that grows well (and keeps well) in cold Scandinavian weather. Denmark’s Constitution Day is typically celebrated with potato sandwiches—cold boiled potatoes on “really, really dark, dark brown rye bread,” Gold said, with thick butter and sliced radishes—and newspapers often promote this “as a typically quintessentially patriotic Danish food.” At a fancy Copenhagen restaurant in the 1960s, Gold remembered being served a platter of French fries and potato chips, both of which were new, “and the edge of the platter was lined with squeezed-out mashed potatoes—you know, sort of a pretty, pretty line. And then just to be sure—because, you know, three kinds of potatoes is not quite enough—there was a bowl of boiled potatoes.”

But even the potato itself was once new. Like the chili pepper—its cousin in the nightshade family, along with the tomato and tobacco—the potato originated in South America, and did not exist outside the New World until the arrival of Europeans at the end of the fifteenth century. And like the chili, the potato was shunned by Danes for centuries.

“At first it was, ‘This is food for animals,’” said Gold. “‘These are poisonous—they are members of the deadly nightshade family.’” It wasn’t until the end of the 1780s that a big landowner named Bernstorff decided to change the minds of the peasants on his property, Gold said. “He literally took a potato and threw it in the fire and then pulled it out and ate it and didn't die to show that ‘Guess what, guys? This isn't poisonous!’” And the rest, as they say, is history. Within 100 years, the potato had taken over.

Denmark may have had conservative tastes, but that’s not to say it was some closed-off hermit kingdom. Throughout these centuries, Denmark was an empire (if a small one), its territory extending from Norway, Iceland, and Greenland to the Virgin Islands, which it held until 1917. But the spicy Caribbean cuisines of St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix did not apparently alter the diet of colonizing Danes. Instead, the Virgin Islands were used for large-scale sugar plantations, Gold said, perhaps feeding Denmark’s taste for sweets.

Potatoes and sugar, it seems, were where Denmark drew the line. Other, milder New World crops, like corn and squash, failed to penetrate the Danish peasant economy. “You're living on the margins,” said Gold. “You got three bad years in a row and forget it—I mean, that's it. So you tend not to experiment with new stuff.”

By the 1960s, potatoes had won. But the 1960s are also when Denmark began to change, because that’s when Chili Klaus was born. Claus Pilgaard, as he’s officially known, grew up in the middle of Jutland, the peninsula that connects with mainland Europe, on a diet of “regular, normal Danish food: beef and potatoes,” he told me. “It was quite exotic to experience garlic.” For university, however, he went abroad to London—and visited an Indian restaurant. “And for the first time I experienced what I would call very spicy—very, very spicy—food.” Immediately, he was addicted.

When he returned to Denmark, however, he was lucky to find any peppers at all, and those he found were hardly spicy. Occasionally, he’d get his hands on a jar of pickled jalapeños, the kind you’d maybe put on pizza. It was like this, he said, for decades. By the early 2000s, Pilgaard (who worked as a musician and performer) had found just 10 or 20 Danes who shared his obsession. They met via private blogs to discuss this state of affairs. They were, he said, geeks, though not looked down on by other Danes— chilies were still too unheard of to even be considered strange.

About a dozen years ago, Pilgaard began growing his own chilies, using seeds he bought on the internet. “What I found exciting is that chili peppers are in all kinds of colors, shapes, flavors, and, of course, different heat levels,” he said. “And they are so easy to grow even in the northern part of Europe.”

Soon he started making YouTube videos in which he’d share violently spicy peppers with Danish celebrities—and he was no longer Claus Pilgaard. He was Chili Klaus, bringing the joy of spice to the good little boys and girls of Denmark. In just the last six years, the dapper, bearded, charismatic Klaus has amassed millions of views, particularly on stunts in which a classical orchestra, say, or a boys’ choir attempts to perform while consuming some of the world’s hottest chilies. And his fame has spread overseas, too: He’s been a guest on Hot Ones, in which host Sean Evans interviews celebrities as they eat chicken wings slathered with increasingly fiery sauces.

Chili Klaus’ videos tap into something very Danish—the tension between stylish, laidback coolness and the craving for extreme, perhaps vulgar experiences, like Viking strongman competitions. “Noma is a wonderful, wonderful restaurant. It’s so delicate, it’s so fine and so special,” he said. “And then there's something suddenly coming with a little bit more crazy” —chilies with names like Reaper and Scorpion and Infinity and Apocalypse. “It's a very exciting food to put into in nearly any dish.” Today, he said, chilies are finding their way into everything in a supermarket, from cheese to juice.

And because they’re new in Denmark, they feel like a real novelty. “Everything on the planet today is discovered already,” said Chili Klaus. “So instead of finding the new highest mountain, I was thinking that we go the other way, to find small things which have never been told about before. It could be insects”—Noma famously serves ants on beef tartare—“or, yeah, chili peppers.”

The only problem with chilies’ recent success in Denmark, he noted, is that newbies can go too extreme. “I have a little web shop, and when people buy spicy things from me, they always pick up the hottest one,” he said. His Carolina Reaper sauce—made using the world’s spiciest pepper—is one of his best-selling. “And that’s maybe also my fault—maybe I should come down a little bit in my videos instead of eating all this.”

So, maybe Denmark missed out on a few hundred years of spicy dining. But at least now we get to witness a country of enthusiastic eaters evolve, in real time, into chili-munching maniacs. If tomorrow I have to flee the United States, I think the Danes will be ready for my Sichuan restaurant. In fact, it looks like I won’t even be the first.